The fast fashion industry is a game of speed, trend, and high-stakes risk. At the heart of this volatile ecosystem lies the single most critical decision for any new product: determining the initial production batch size. This decision is not just a logistical choice; it is a primal business gamble that determines profitability, brand perception, and operational agility.

For a fast-fashion brand, a new style is like a firework: it is launched quickly, burns brightly for a short, unpredictable time, and then fades. The challenge is that the initial order must be placed before anyone knows if that firework will be a damp squib or a global smash hit.

This necessity creates the “Small Batch, Big Problem” paradox: while a small batch protects a brand from financial ruin, it dangerously exposes them to the crippling loss of a runaway success. Our discussion will explore this perilous balance, the financial consequences of getting it wrong, the sophisticated strategies employed by giants like Zara and H&M, and how cutting-edge technology and domain expertise are essential to mastering this challenge.

Defining the Initial Batch Size Dilemma

The initial batch size production estimation problem is the process of calculating the preliminary order quantity for a new apparel style that has no prior sales history. In the fast-fashion context, this is a distinct challenge due to the specific characteristics of the business model.

The Core Volatility of Demand

Fast fashion thrives on demand volatility. Trends are fleeting and often emerge from unpredictable sources like social media or celebrity sightings. Unlike a classic product with stable, predictable demand, a fast-fashion item can be a global hit one week and obsolete the next. This makes traditional, linear forecasting models ineffective. The core problem is accurately quantifying the unknown demand for a product that will have a product life cycle lasting mere weeks.

The Short, Unforgiving Product Life Cycle

The window of opportunity to sell a fast-fashion item at full price is incredibly brief. If the initial batch is insufficient to meet peak demand, there is often no time for a second production run to capitalize on the lost sales. This lack of a “second chance” makes the accuracy of the first, initial order paramount.

The Trade-off of Risk

The initial batch decision is fundamentally a balancing act between two types of risk:

- Financial Risk (Cost of Overage): The risk of producing too much inventory that ultimately needs to be sold at a deep markdown or written off as deadstock. This is a direct attack on profit margins.

- Market Risk (Cost of Underage): The risk of producing too little inventory, leading to stockouts, which results in missed sales, customer dissatisfaction, and potentially drives customers to a competitor.

The goal is not to eliminate risk, but to place a calculated initial bet that provides enough product to test the market, without committing excessive capital.

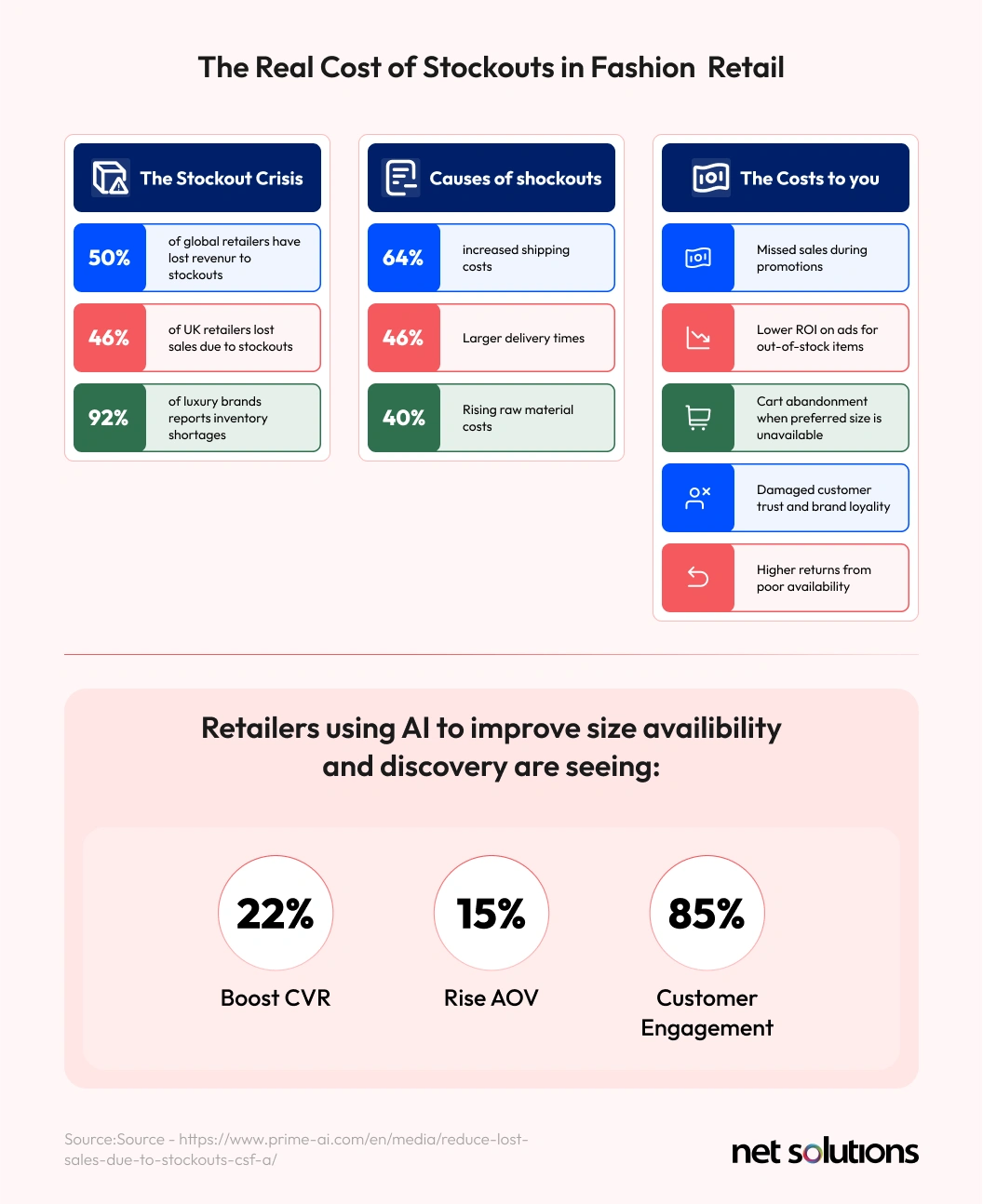

Quantifying the Cost of Error

An incorrect initial batch size calculation results in direct, quantifiable losses, which define the financial pressures in the fast fashion supply chain. These are broadly divided into the Cost of Overage (buying too much) and the Cost of Underage (buying too little).

Loss from Overstocking (The Cost of Overage)

This is the most feared outcome in fast fashion, as it represents a permanent erosion of capital and margin.

- Markdown Loss (Direct Revenue Loss): The core financial penalty. Any item not sold at its initial Full Retail Price (FRP) must be heavily discounted. The loss is the difference between the FRP and the final Clearance Price, multiplied by the excess quantity. This markdown often leads to selling the product below its initial cost, resulting in a loss for the company.

- Deadstock Costs (Total Capital Loss): Inventory that is completely obsolete, even at deep discounts, must be written off. This is a total loss of the initial Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). In many cases, these items are liquidated, donated, or disposed of, incurring further administrative and logistical expenses.

- Carrying/Holding Costs: The logistical expense of storing the unsold inventory (warehouse rent, insurance, handling, security) until its final disposition. This continuously eats into the profit margin of otherwise healthy items.

- Brand Devaluation: Frequent, aggressive markdowns train consumers to wait for sales, eroding the brand’s perceived value and its ability to achieve a high Full-Price Sell-Through Rate (FPS) in the future.

Loss from Understocking (The Cost of Underage)

While less visible on a balance sheet than a markdown, the loss from understocking is equally damaging to growth and market share.

- Lost Sales and Profit (Opportunity Cost): The most immediate loss is the profit margin from a sale that could have been made. Since the trend window is short, the brand cannot recover this revenue through subsequent reorders.

- Customer Churn and Dissatisfaction: Customers who experience a stockout are highly likely to seek the product from a competitor. This results in the loss of that Customer’s Lifetime Value (CLV) to the brand.

- Expediting Costs: If the brand attempts an emergency reorder to meet a clear demand signal, they often incur higher production costs and expensive air freight charges to speed up delivery. This increases the unit COGS and diminishes the profit on the reordered batch.

The world’s fast-fashion leaders have developed sophisticated, contrasting strategies that use the initial batch not as a perfect prediction, but as an instant, real-time market validation tool.

The Omnichannel Agility Model: Zara (Inditex)

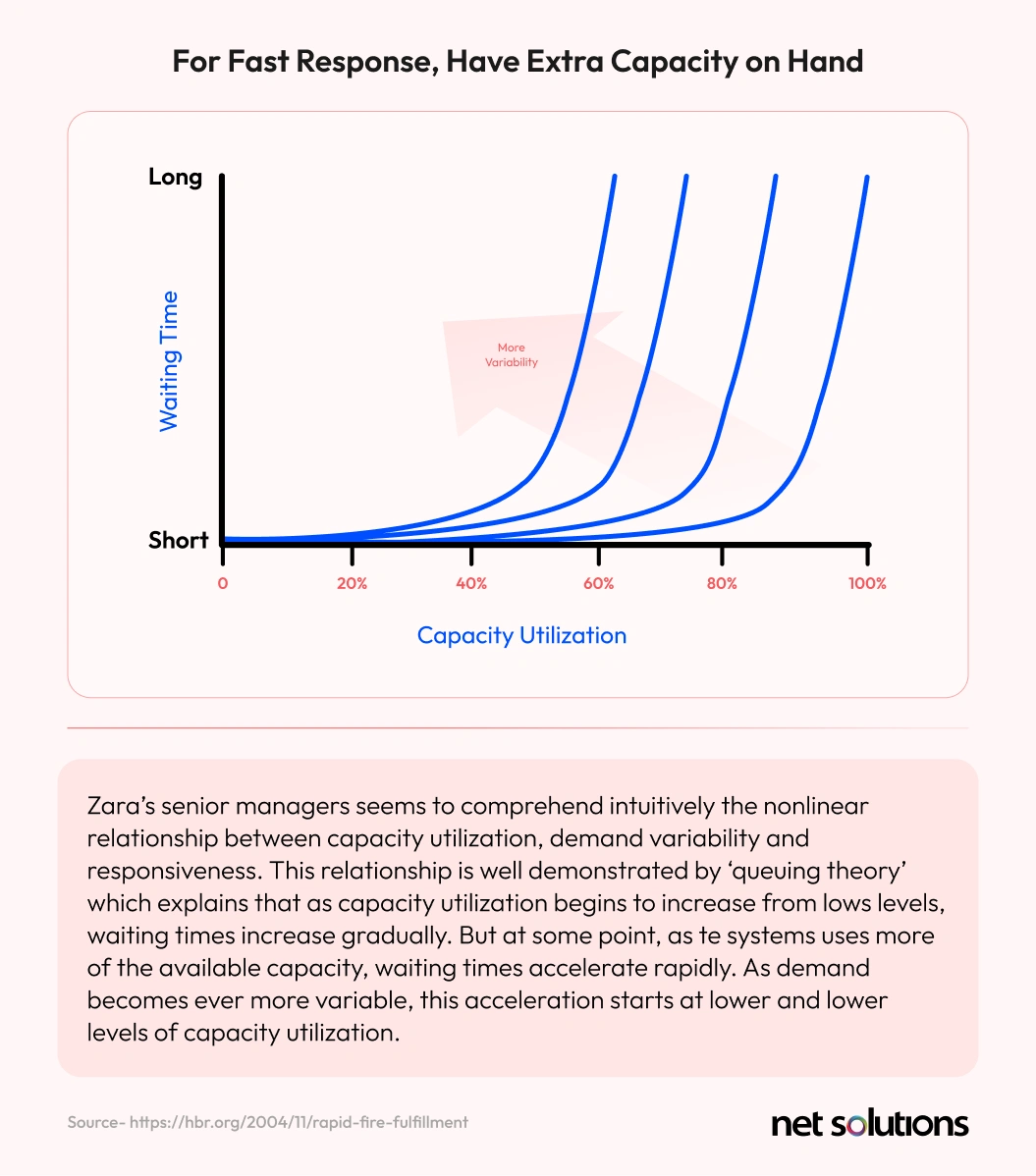

Zara minimizes initial forecast risk by prioritizing speed and vertical integration:

- Small Initial Batch: Zara intentionally places a conservative initial batch (e.g., 15-20% of potential total volume) to get the product into stores quickly. This acts as a pilot program.

- The Data Feedback Loop: Store managers and sales associates gather real-time data—both POS sales and qualitative feedback (what customers ask for but cannot find, which is the key to measuring lost sales).

- Near-Shore/Vertical Production: A large portion of their production is centralized or near-shore (e.g., in Spain and surrounding countries). This proximity allows Zara to initiate a reorder on a successful style with a lead time of just 2-4 weeks.

- Result: Zara achieves a high Full-Price Sell-Through Rate by creating scarcity and only committing to large volumes after market success is proven.

Solving the Initial Batch Problem with Advanced Technology and Domain Expertise

The future of fast fashion forecasting lies not in intuition, but in creating a predictive architecture that supports the brand’s unique agility. Bridging the gap between sophisticated data science and the commercial urgency of the buying team will become a core value proposition for any fast fashion brand.

Multi-Factor Probabilistic Forecasting: Beyond simple statistical extrapolations, Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning model ingest data from hundreds of sources, providing not a single forecast number, but a range of demand with a quantifiable confidence interval. This is critical for calculating the financial risk (Cost of Overage vs. Cost of Underage) for every potential batch size.

External/Causal Data Integration: Break the “internal data silo” and integrate external drivers that move fast fashion trends:

- Visual Trend Analysis: Use AI to recognize new silhouettes, colors, and patterns emerging on social media (e.g., Instagram, TikTok) and competitor websites.

- Search and Intent Data: Analyze real-time search volume and velocity to gauge unfulfilled customer interest.

- Micro-Climatic Data: Incorporate localized weather forecasts, which heavily influence sales in apparel.

Pragmatic Domain Implementation: From Model to Margin

A model is useless if it cannot be operationalized by a buyer under a tight deadline. An integrated approach ensures that the technology directly supports profitability:

Real-Time POS Feedback Loops: Robust data pipelines are required to ingest Point-of-Sale (POS) and inventory data in near-real-time. This powers the crucial second decision: Should we reorder a winning style, and if so, how much? This system turns the initial batch into a live, continuous learning exercise.

Sourcing Strategy Integration: Segment forecasts based on the brand’s lead-time capabilities (e.g., 4-week Agile Sourcing vs. 12-week Traditional Sourcing). The confidence required for a 12-week buy is much higher, and the recommendations reflect this structural risk.

Turning Volatility into a Competitive Advantage

The fast fashion industry’s foundational risk—the inability to perfectly predict initial demand—is not going away. However, the world’s leading brands are proving that this volatility can be managed and even weaponized as a competitive advantage.

The shift is clear: from trying to predict everything to being ready to react to anything.

For brands looking to minimize devastating markdown losses and maximize the profit from their next viral hit, the answer lies in embracing a data-driven culture. This requires moving beyond spreadsheets and siloed data to implement a sophisticated forecasting architecture. By combining advanced AI, real-time data integration, and a deep understanding of the fast-fashion profit mechanics, we empower brands to make that critical “small batch” decision with a high degree of confidence, ensuring that every successful trend generates a big, beautiful profit.